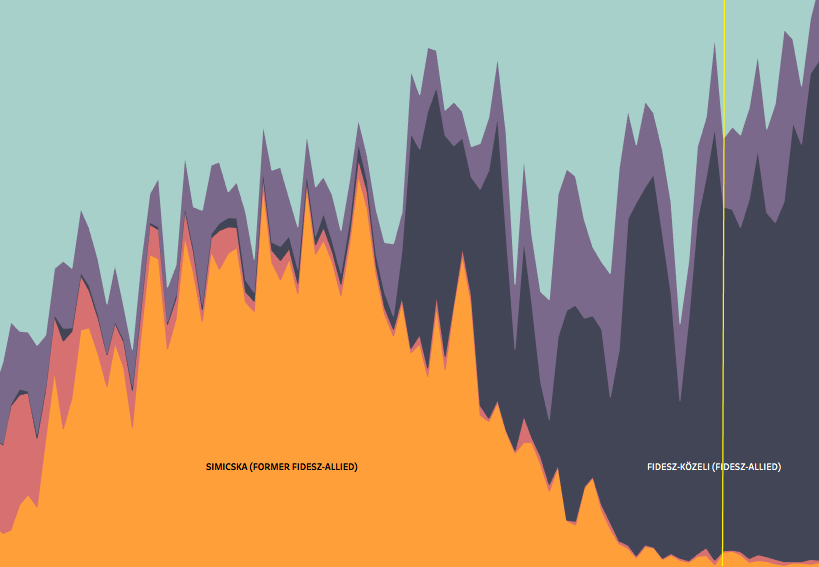

State advertising spending in the market for public affairs weeklies

The impact of the 2010 election was also spectacular in the market for political/public affairs weeklies: Heti Válasz, which is affiliated with Lajos Simicska, practically monopolised the state funds expended in this sector.

If we look not only at the percentage of spending allocated to individual outlets but also at the total forint amounts, then we see that this sector, too, was marked by extreme fluctuations. Especially after 2010 it was very unpredictable how much state money would be allocated to each paper. It was also apparent that for several months in 2015 the state spent little to no money in this market segment: the role of Heti Válasz declined after the Simicska conflict, but since no new pro-government weekly was launched, there was nowhere to spend the money. In the segment of weekly newspapers Figyelő, which was acquired by Mária Schmidt at the end of 2016, practically receives all the state advertising.

The distribution of state advertising spending in the television market

It is instructive to compare how television channels’ competition for state advertising funds has evolved in this area.

As is apparent, the growing share of TV2 (in black) in the state advertising market is striking. Until the end of 2013, RTL and TV2 received roughly the same share of state advertising. At that point, however, two company executives, Zsolt Simon and Yvonne Dederick, bought the holding company from the owner, the German Pro7Sat1 group. Subsequently, the share of the TV2 group surged to 70-80% of total state advertising in the television market, and it has held steady at this level, only dropping to 30-40% in the first half of 2015, when media reports suggested that the government was pressuring Simon and Dederick to sell their shares in the television channel to Andy Vajna. This deal was ultimately concluded in autumn that year, and TV2’s share in state advertising spending returned to its new “normal”.

The distribution of state advertising spending on the outdoor market

It is in the outdoor advertising market that the impact of the change in government in 2010 was most pronounced. International companies were relegated to the background, while state institutions practically poured public funds into companies controlled by Lajos Simicska.

It is important to note that this market was subject not only to an internal reallocation of funds but was also the target of a massive increase in the amount spent by the state on advertising. One of the reasons may have been that Simicska’s companies allowed for a cost-effective way for funnelling taxpayer money into favoured private hands (there are basically no costs for producing content in this market – one only needs some creative design for ads and to put them on posters). Another reason may have been that the Fidesz government has been more deliberate in its use of this particular form of political communication. Outdoor advertising can also reach segments of the public who do not consume public affairs content or make a deliberate effort to avoid pro-government media. That is why it has become an often-used communication instrument in recent years.

After the public break between Orbán and Simicska, the companies owned by the latter fell out of favour in this market as well. Until the point when a major outdoor advertising company will be taken over by a businessman with close ties to the government (the ESMA- Hungaroplakát portfolio held by the businessman István Garancsi is too small for this purpose), the government will have no choice but to spend the money on outdoor advertising at the French-owned company JCDecaux.

The distribution of state advertising spending on the radio market

The history of state advertising spending in the radio market followed a somewhat different trajectory from that observed in the other sectors. The inflection point was not the change in government in 2010 but the frequency tender for national commercial radio stations in 2009. As a result of the tender, two stations active at the time, Danubius and Sláger, lost their frequencies, while in November 2009 two new, Hungarian-owned radios, Class FM (operated by Advenio Zrt) and Neo FM (operated by FM1 Zrt) began to broadcast on the same frequency.

As is well-known, the frequency tender was based on a backroom political deal, and Class FM, affiliated with Lajos Simicska, became the target for the allocations of vast amounts of public funds. At the same time, Neo FM, whose owners had ties to the Socialist Party (which was in opposition after 2010), hardly received any state advertising. The station became financially unviable and ceased operating in the autumn of 2010.

Another striking disproportionality was manifested in the gap between the respective revenue from state advertising spending received by two Budapest talk radios, the right-oriented InfoRádió and the openly leftwing station Klubrádió. Despite the fact that Klubrádió has more listeners, InfoRádió received more money. State advertising spending allocated to InfoRádió has been rather stable over the past 10 years, regardless of whether the government was leftwing or rightwing. Yet as the rightwing government entered into office in 2010, Klubrádió now longer received any state advertising funds.

Here, too, the impact of the Simicska scandal is readily apparent. Though the amount of state spending in this sector began to decline from the time of the Simicska-Orbán break in early 2015 until the end of the same year, as of 2016 the public media radio stations and Sláger FM, which was approached by businessmen with ties to Fidesz, took the place previously held by the Simicska-controlled Class FM. At the end of 2016, Andy Vajna launched his new radio network, Rádió 1 and he gained significant share of state advertising in a short time.

The distribution of state advertising spending in the online market – Origo vs Index

Spectacular changes in state advertising spending in the digital media began only in 2012, relatively late when compared to other sectors.

The first beneficiary was index.hu, which was then supplanted by origo.hu as the prime benef

iciary. Though Origo was only acquired by the pro-government New Wave group at the end of 2015, the online newspaper took over the position as the leading target of state advertising spending in its market segment from the Index group already in May 2014. A month later the Origo scandal broke, and from them on Origo essentially became hegemonic in this market, save for the few months when it was bogged down in speculations about its sale, a process that ultimately resulted in its acquisition by business interests associated with Fidesz.

The share from state and commercial revenue at individual media brands

The graphs below present how each company did relative to other companies and in absolute terms in attracting commercial and state advertising revenue, respectively (the graph allows you to set different years).

The share of state-sponsored and business-sponsored advertising, respectively, is manifest in the figure below. Media companies marked with light blue in the individual years are those with a relatively low share of state advertising spending. The further we move up in the column, the greater the role of state-sponsored advertising. The lines that separate the various levels (25%, 50%, 75%) are also highlighted by the distinct colours used.

One can see here that media outlets with close ties to the governing party are often marked with the colour orange (a share of 25-50% of state advertising in their total revenue from advertising), but from today’s vantage point it is somewhat surprising that between 2007 and 2009 Magyar Nemzet – which was at the time the flagship daily of then-opposition Fidesz party – fell also into this range. The State’s favourite outlets fall into the red and black segments. There were three print media in 2017 without commerical revenues, so the share of state advertising revenue was 100% at these media outlets.

The last two graphs are similarly illustrative. It is readily apparent in this table that for most media brands, advertising revenue was low, no matter what the source (e.g. state or commercial). The companies which are close to the horizontal Y-axis but are further from the graph’s zero intersection point boast a higher amount of commercial revenue than the other media and typically live off the market (orange colour). Those that are moving to right (dark blue) and have higher values in state dimension than the majority of media realised greater revenue from the state.

The other graph presents the percentage of total advertising from state and commercial revenues. These ratios are zero-sum, that is an increase in the total share of advertising by either commercial or state revenues will inevitably lead to a commensurate drop in the value of the other. The closer an individual media outlet is to the lower right-hand corner, the more of its advertising revenues stem from the market (for then its revenue from commercial advertising is near the 100% mark, while money from the state is around 0%). A ratio of 40-50% can be considered very high, but a share exceeding this level means that the state essentially sustains the media outlet in question.

Conclusion

As the graphs show, the changes in state advertising spending also illustrate the underlying political processes. Under the centre-left government before 2010, the spending of state institutions was more balanced, but after the election of 2010 media owned/controlled by Lajos Simicska began to completely dominate the state-funded segment of the advertising market.

The 2014 election did not lead to a change in the political landscape, but it was marked by the conflict between the prime minister and Simicska, which came to the attention of the wider public in February 2015. This led to a comprehensive redistribution of state advertising spending, the Hungarian media landscape has been changed in a short time. New media outlets were launched, others were acquired by pro-government investors. This new structure created the media background of the Fidesz for the 2018 election.

Data: Kantar Media

Data visualisations: Attila Bátorfy

Text: Ágnes Urbán, Gábor Győri

Támogasd a munkánkat banki átutalással. Az adományokat az Átlátszónet Alapítvány számlájára utalhatod. Az utalás közleményébe írd: „Adomány”, köszönjük!